- Home

- Richard Thompson

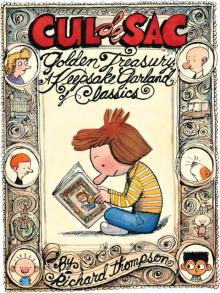

Cul de Sac Golden Treasury

Cul de Sac Golden Treasury Read online

Cul de Sac is distributed internationally by Universal Press Syndicate.

Cul de Sac Golden Treasury copyright © 2010 by Richard Thompson. All rights reserved. Printed in China. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information, write Andrews McMeel Publishing, LLC, an Andrews McMeel Universal company, 1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106.

E-ISBN: 978-1-4494-0041-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009943357

www.andrewsmcmeel.com

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND BUSINESSES

Andrews McMeel books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write to: Special Sales Department, Andrews McMeel Publishing, LLC, 1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106.

[email protected]

Introduction

In French, “cul-de-sac” means “bottom of the bag”; it’s not a particularly nice phrase—the “bottom” part refers more to “your own personal rear end” kind of bottom. I didn’t know this when I first thought of naming a comic strip set in the suburbs Cul de Sac. All I knew was that a cul-de-sac was a little dead-end turnaround popular in suburban developments, and that I thought I knew them well, having lived on several when I was growing up.

Since starting the strip, I’ve learned not only the French translation, but also the fact that cul-de-sacs (the dashes are more idiomatically correct) are now considered bad design in community planning; it’s been found that they promote insularity, fail to foster a feeling of community, and are a wasteful, poor use of land. Also, they may contribute to childhood obesity. So, despite having a few early doubts, I couldn’t have picked a better name for a comic strip.

Cul de Sac started as a weekly strip in the Washington Post Magazine. Some of these early strips have been included in this collection.

For Tom, Lee, and Greg, who made me do all this.

This drawing is a combination of the haunted, crazily leaning town from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and the huge wall from King Kong. I didn’t realize this at the time I drew it, but the best ideas are often unintentional. And it makes perfect sense as I have always loved old horror movies.

“Bliss” is her first name, though I haven’t yet discovered her last name. Sometimes you have to let your characters reveal themselves gradually, which is a nice way of saying that sometimes you have to wait until you can think of an appropriate funny name.

There were several versions of this. One had Beni saying, “Look, the Wild Things found Waldo! How grisly!” I kinda wish I’d kept that one in.

Most preschools don’t have anything as formal as a back-to-school night for parents. This is just another sign of Blisshaven’s forward-looking, progressive character, and Miss Bliss’s delusions of grandeur, too.

Throughout the strip, Alice has a love-hate relationship with reading. Given the power of words, it’s probably a healthy attitude, but I don’t envy her future teachers.

That’s probably Dill’s mom warning Mrs. Otterloop about her juice mustache. It’s the only time I’ve seen her.

Years ago, I read an interview with Maurice Sendak where he said that in Charles Dickens’s books, everything is alive—every chair, spoon, door, the fire in the fireplace; everything jumps to life and has a personality. This is a logical extension of that. And you’ll notice that the personality of the comic strip is snide and unlikeable.

Three car strips in a row. What can I say? Cars are fun to draw.

The rattiness of Alice’s hair peaks in this strip. Maybe somewhere along the way, she grabbed a hairbrush.

The modern playground as a monster-sized digestive system. Another fun thing to draw!

Mr. Danders has a touching if overinflated estimation of his own personal accomplishments. And who can blame him? He deserves at least a BA.

Polyfill is based on a real toy that began life as a doggie chew toy.

Beni is based on my brother Tim, whose mechanical bent was apparent from about the age of three, when my mom had to pull him out from under a grocery store freezer unit where he’d crawled to find out how it made things cold. I think Tim had more talent with a hammer, though he wasn’t necessarily trusted with one.

At Alice’s age, I was almost convinced that I could control bees with my mind. Or at least offer them friendly advice.

Timmy Fretwork is based on roughly five people. More recently in the strip, it’s been revealed that he and Miss Bliss are an item, and that he’s something of a jack of all trades, though he’s not particularly adept at any of them. Several teachers of lower grades have told me that this is a frighteningly accurate portrayal of classroom behavior.

When I was small, we had solid, hard-packed dirt to stop our fall off playground equipment. Nowadays they’ve got cushioning beds of mulchy stuff that erodes easily, leaving the above-mentioned hazard to deal with. I ask you, which would you rather fall on?

This is the only glimpse so far of Dill’s father. And no wonder.

It’s usually a warning sign if I laugh at an idea I have. Chances are good that, on second glance, the humor that seemed so ingenious will have evaporated, leaving an empty and embarrassing shell of a joke. This one’s an exception; it makes me laugh every time I read it. Now, having said that, I’m scared to read it again.

This sums up Alice pretty nicely in three action-packed and slightly gruesome panels. And I think having the ability to throw your own head in a fit of passion is a pretty universal yearning.

Quite a few of the Sunday strips from Cul de Sac’s first few years as a syndicated feature were redrawn versions of strips that originally ran in the Washington Post Magazine. Such as these two, for instance. The one below was a lot of fun to draw—all those variations on Alice’s face from cubist to cloying. And in both, the action reaches its peak offstage, leaving the reactions afterward to carry the humor.

More fun with Alice’s head (see two preceding pages). This seems like a pretty good example of my talent for depicting the thought process of a four year old. It’s a facility that worries me more than a little.

Halloween has almost more glamour for kids than Christmas, I think.

Nora, being four and a half, is more sophisticated and accomplished than Alice, and she somewhat intimidates Alice.

I like the perspective of the sidewalk in the first two panels. It gives a nice visual “oomph” and it lets me cram all that stuff into the first panel in an interesting angle. Cramming stuff into little panels is, let’s face it, the hardest part of drawing a newspaper comic strip.

If you watch her, Mrs. Otterloop is often doing odd chores: carrying things, fixing things, writing things—nothing too odd or weird, but nothing too easily identifiable. This is how I imagine a child views a parent: someone who’s always busy at some activity that the child doesn’t understand or much care about.

There’s an ancient creation myth from some lost culture where a god has a little lump of leftover, unanimated clay, but he drops it and it rolls under a table where he can’t get to it. He says, “$%^#, forget it; it’s not worth the trouble.” And then the lump wakes up and it’s the first guinea pig.

The weaponizing of good intentions, which should be a subtitle for something.

Petey eventually becomes a master of the shoe-box diorama, effectively cramming all of human history into a space that’s 12" x 7" x 4". Here he’s just trying to think outside the box.

Interestingly, PT is code for Petey.

Grandma has lived so long with Big Shirley that she’s gone a little feral.

Though I agree abou

t the beets.

I once thought of adding two characters—a lawn gnome and a pink flamingo who ran a lawn service, only nobody wanted them anywhere near their lawns because lawn gnomes and pink flamingos are tacky. It’s an idea that deservedly went nowhere, but it’d make a great animated movie. Hello, Pixar?

These two strips are related in that they mess around some with the comics form. In the strip above, Alice cannot be convinced that the cat strip is sequential. To her, it’s all occurring simultaneously, in the here and now, which is appropriate for her character.

It’s fun and interesting to play with time in a comic strip. Each panel is a minute slice of time, and the space between them can be nanoseconds or eons. Sometimes the space between the panels is more important than the panel itself. Which is a boon if you happen to be lazy about drawing.

The word “cheese” is comedy gold, at least among children. So is the word “pants.” “Cheese pants” would be comedy gold of almost blinding brilliance.

Marcus DeMarco is an only child. He needs a sibling to siphon off some of his mom’s high expectations.

Petey and food have an uneasy relationship. In fact, he’s a world-ranking picky eater, and he’s rather vain about it, too.

Winter hats such as Dill’s do exist and are bought by parents who put them on their child’s actual head. For this, I, as a cartoonist, am grateful.

Admit it—dealing with unknown babies can be awkward.

This strip provoked one of my first reader complaints. It came from a woman who thought Mr. Otterloop was being abusive. I thought he was merely being clumsy or, like Petey, awkward around those younger than him.

The man in the front row who gets annoyed and leaves was so compelling that someone sent me a fan-art drawing of him. Maybe I should focus on him instead of the Otterloops, but the enigma of his disappearance is what makes him interesting.

Babies and toddlers are rather malignant forces in Cul de Sac. So are grandmas. I can’t account for this, but readers should complain.

Alice isn’t a bad artist for a four year old.

This was drawn almost directly from life. Unfortunately, it was mine.

The largest Christmas sweater ever made was a forty-pound behemoth that featured lights, ornaments, tinsel, an animated nativity scene, dancing snowmen, and mixed choir and soloists. The unfortunate wearer had to be wheeled around like a parade float.

Inasmuch as the Otterloops live in a fairly new development, that shrub must predate their house.

Moms have sweaters; dads have hats.

Santa Claus commands a lot of awe and fear in children, even those that don’t necessarily believe in him. So do clowns, but they don’t have that religious/moral thing going on.

There’s a weird pathos to unclaimed, lost, or unwanted toys, even those that are misguidedly educational, such as this one.

Please note Alice’s feet-splayed sitting position, common among small children (though not adults, who can’t do it). Just another example of the accuracy that Cul de Sac strives for every day.

Thus begins one of Dill’s many minor obsessions.

Once, in the parking lot of a big-box store, I saw a train of carts go by, towed by a small, beeping vehicle with flashing lights all over it. The head of every child present swiveled around to admire it, and those of most adults, too. The glamour of driving such a thing was overwhelming.

This pretty much sums up my whole view of family life. I could just stop right here and figure I’ve said enough and anything else is just an elaboration, but I won’t.

No one ever calls Mr. Danders anything but “guinea pig,” and I’m sure it annoys him no end. “Gweep” is as accurate as I could get in transcribing the noise that guinea pigs make.

This launches one of several miniature epics where Danders escapes or is otherwise ejected from his cage.

In each strip in the series, Danders assumes a new identity, or is mistaken for something else. His protean nature and knack for easy assimilation may be his greatest defenses. Or more likely, he’s just so bland that nobody gives him much of a second glance.

Wasn’t that epic?

For years, I lived close enough to the county fairgrounds that I could hear the tractor pulls and demolition derbies (I couldn’t quite smell the livestock though). Please note the cow-tipping gag.

I salute you, Family Circus!

Many people can do actual creative work in a coffee shop, which impresses me as glamorous and bohemian. I can’t; I’m easily distracted and I can barely think straight if there’s another person in the room. And as for sketching in a public place, forget it. I hate to admit it, but the prospect of being caught in a creative act mortifies me.

Another Danders epic, this one a comic tragedy of love and loss.

FedUPS struck me as hugely funny when I thought of it four or five years ago. I’m still waiting for a laugh, and it’s probably too late. I’m sure it’s been independently thought of hundreds of times by now by other, funnier people. Sometimes, if I think of something like this that strikes me as hugely funny and original, I’ll type it into Google and discover thousands of hits.

Please note the knuckle tattoos.

That was epic, too, wasn’t it?

This is Ernesto Lacuna, Petey’s sort-of friend who may be imaginary (more on that later). His name is a pun on the great Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona and the word “lacuna,” which means “gap or missing section.” OK, so maybe that’s a little too clever, but it fits him; he’s kind of an enigma, and kind of a James Bond villain in embryo. I haven’t decided whether he is imaginary or not, and I don’t think I ever will.

A passive-aggressive fistfight strikes me as funny.

I grew up around Washington, D.C., and Cul de Sac was originally more explicitly set there. This kind of encounter is pretty common, especially the name-forgetting part.

In the earlier version of Cul de Sac, Petey played the trombone, but I changed it to the oboe when it went into syndication. The trombone was funny as it’s loud and demonstrative, with all that elbow-throwing slide action; it was therefore counterintuitive for Petey, who aims to be unobtrusive. But trombones are hard to draw, so it’s “Hello, oboe!”

I salute you, Lemony Snicket.

The habit of turning all sentences into questions by ending them with a rising inflection is called “uptalking.” Small children do it, and adults, too, to provoke a response and ensure that they’re being paid attention to. It’s probably a sign of insecurity.

This is a very accurate depiction of a DC Metro train, and of how I would act if I suddenly bellowed “pufferbellies” into a cell phone.

Eskimos actually only have a few words for “snow,” like the man said. The notion that they had lots of words for it has a lot of charm though.

This little adventure is drawn almost directly from life, alas.

Nara was called “Narjeel” for a while, maybe because of a slipup on her registration form.

Among them, Dill’s numerous brothers possess almost all the skills known to man, many of dubious legality.

Speaking of skills, nose blowing is a learned skill, and not an easy one.

Dill’s a pretty good artist for a four year old.

Random self-absorption—a sure sign of four-year-oldism.

That Time-Out Corner seems to see a lot of visits by group tours.

This was, as they say, inspired by a true-life incident.

Please note the uninspired, stunted snowmen. These are the types I believe are more often built by small children who lose interest fast and can’t be bothered to build the more complex three-part classic snowmen. And forget the carrot nose and coal eyes, or the scarf and top hat. Who can even find that stuff anymore?

Cul de Sac Golden Treasury

Cul de Sac Golden Treasury